Annoying. Scratchy. Disinterested. Sexist. Innovative. Unprofessional. Vocal fry is all over the opinion pages lately, despite being a far-from-new phenomenon.

This ‘popping’, drawn out style of speech was first recorded in British men in the 1960s, who – it’s thought – were trying to exert a sense of social superiority.

So why is vocal fry on the tip of everyone’s vibrating vocal chords today? Because, of course, what has changed in recent years is who’s using it and who cares.

The sound of science

So, what exactly is vocal fry? Let’s watch, listen and learn:

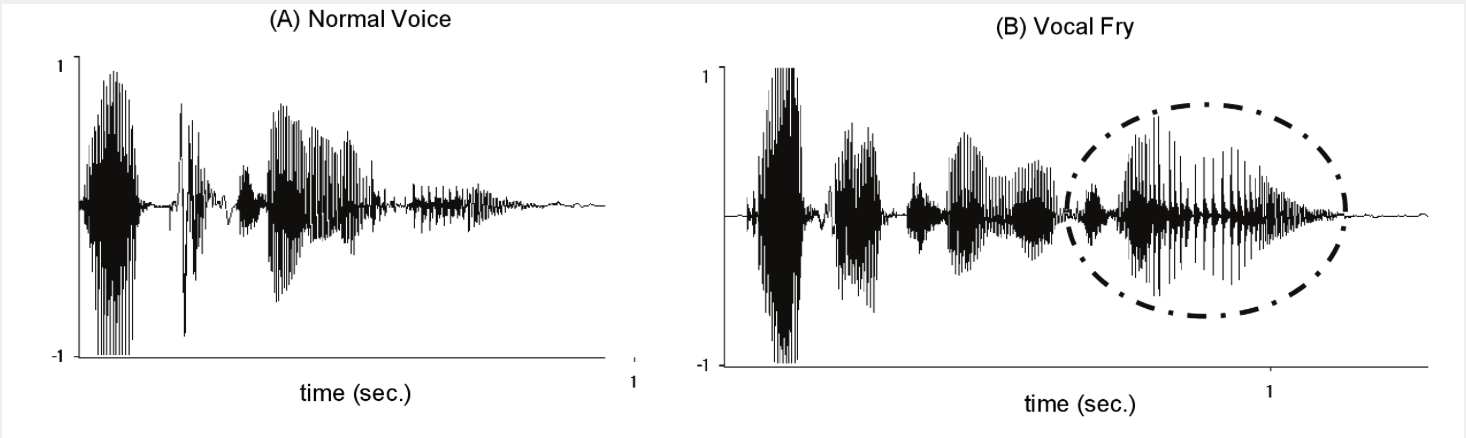

Getting a little more scientific, a recent study in the open-access journal PLOS ONE (The Public Library of Science ONE), included a figure showing the waveform of vocal fry, with the ‘creeeaaakiness’ circled:

In effect, the speaker is using a lower register than they would naturally causing the vocal chords to vibrate more slowly and at the same time are often drawing out their words as they croak.

So, what does all this have to do with business?

Women at work

The reason vocal fry matters is that the study we mentioned earlier actually focuses on people’s impressions of vocal fry: the judgements people make about the individuals who deploy it.

The title of this research paper was, ‘Vocal Fry May Undermine the Success of Young Women in the Labor Market’ and it ended up concluding that:

Relative to a normal speaking voice, young adult female voices exhibiting vocal fry are perceived as less competent, less educated, less trustworthy, less attractive, and less hirable. The negative perceptions of vocal fry are stronger for female voices relative to male voices

Significantly, it didn’t find that men didn’t exhibit vocal fry, but that those who did weren’t judged as harshly as the women who did. So vocal fry at work is bad. Or is it?

For women (and men) in pitches and negotiations, the question is much bigger than simply to fry or not to fry.

Who’s judging?

The question we need to ask is, if back in the 60s vocal fry was a symbol for superiority in men, why is it now seen as a sign of inferiority in women?

Casey A. Klofstad, one of the authors of ‘Vocal Fry May Undermine the Success of Young Women in the Labor Market’ points out that ‘humans prefer vocal characteristics that are typical of population norms.’ Women who use the low tones of vocal fry buck this trend, perhaps accounting (at least in part) for the fact that women’s vocal fry is less palatable than men’s.

In part it could also be down to the origins of the current surge in vocal fry, which is often traced back to female pop stars of the early 2000s. Think Britney Spears or Ke$ha:

[youtube url=http://youtu.be/CduA0TULnow?t=39s]

Then of course came the Kardashians and quirky-girl Hollywood stars like Zooey Deschanel. None of these examples exactly scream boardroom professionalism (although interestingly they are examples of extremely successful women).

This is only half the picture though. The video at the top of this article also referenced ‘uptalk’ as popularised by Valley Girls in the 1980s. This was another vocal trend that swept across the nation (and the Atlantic), creating a generation of young women who, it seemed, could only ask questions.

Again, the origins were Hollywood characters and the like, but as the uptalk took over, its significance changed. Speaking to the New York Times for an article praising young women’s innovative uptake of vocal fry and its predecessor uptalk, Dr. Eckert of Stanford said:

‘Language changes very fast,’ and most people — particularly adults — who try to divine the meaning of new forms used by young women are ‘almost sure to get it wrong.’

Look a little deeper, as Amanda Ritchart and Amalia Arvaniti did, and you find that many women now use uptalk in the office to preempt interruptions. And vocal fry may well be ‘popping’ up so much for very similar reasons.

Can you hear me through this glass ceiling?

All of this discussion around why vocal fry is heard negatively becomes academic when you look at the bigger picture, which suggests women are being judged on how they speak, rather than what they say.

Men ‘suffer’ from vocal fry too. As a recent BBC article pointed out, former US president Bill Clinton has vocal fry issues, which is ‘something barely, if ever mentioned as a problem for his professional presence.’

And Liam Neeson seems to have taken vocal fry to its crispy, sizzled extreme in his latest film trailer:

[youtube url=http://youtu.be/gznBvoDQYLI?t=10s]

While research shows vocal fry is still viewed less favourably than a clean, un-fried voice in men, it just doesn’t damage their authority or credibility in the same way as it does for women.

‘If women do something like uptalk or vocal fry, it’s immediately interpreted as insecure, emotional or even stupid,’ says Carmen Fought, a professor of linguistics at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. ‘The truth is this: Young women take linguistic features and use them as power tools for building relationships.’

A smokescreen for prominence and power

Could it be that women are using affectations, such as vocal fry and uptalk, to mask their increasing importance in the workplace in an effort to battle sexism and find a way to build their careers without intimidating anyone?

This seems to be what Naomi Wolf suggests in her essay in The Guardian, published earlier this year, which flipped the vocal fry debate on its head.

Wolf is against vocal fry because she sees it as a tool for disempowering women; she sees a generation of young women who have been failed by feminism and haven’t been taught how to handle interruptions and who don’t realise they shouldn’t have to placate their (often male but not always) elders.

It is because these young women are so empowered that our culture assigned them a socially appropriate mannerism that is certain to tangle their steps and trivialise their important messages to the world.

Women are told that deeper voices are seen as more dominant and are more successful at obtaining leadership roles. But go too low in the vocal fry range and you break convention and appear less educated and annoying. It’s a catch-22.

Underlying this, as Wolf suggests, is an attempt to break into what is often still a male-dominated workplace, especially at senior levels, and a lack of confidence in doing so.

She argues that, in order to truly be taken seriously, women need to learn to take control of their voices and claim their power, rather than artificially alter their voices to conform to an expectation. (Yes, there is some irony there.)

So, can vocal fry lose you your next big deal?

The crucial elements for anyone communicating in the professional world are clarity and concision. And of course, empathy. You have to think about your audience and what matters to them; what affects the way they think; and what turns them off.

By that logic then yes, men and women should work to assert a more natural voice that displays confidence and authority and ensure that CEOs and investors know when they’ve finished their sentence and exactly what they’ve said. (In other words, avoid uptalk and vocal fry).

We might, however, be in a moment of transition. Talking on NPR, Dr. Penny Eckert, professor of linguistics at Stanford University and the co–author of the book Language and Gender, said:

I was shocked the first time I heard this style [vocal fry] on NPR. I thought, “Oh my god, how can this person be talking like this on the radio?” Then I played it for my students, and I said, “How does she sound?” and they said, “Good, authoritative.” And that was when I knew that I had a problem.

It’s a particular demographic of people (read white, older, male and privileged) that seem to have the most problem with vocal fry. But boardrooms are changing – albeit slowly – and are becoming more diverse in every way – including vocally.

Writing for Slate, Amanda Hess reports that:

One study recorded a college-aged woman’s voice while speaking in an even tone, and then again when employing the creak. When both samples were played for students in Berkeley and Iowa, those peers viewed the affectation as “a prestigious characteristic of contemporary female speech,” characterizing the creaky woman as “professional,” “urban,” “looking for her career,” and most tellingly: “not yet a professional, but on her way there.”

It’s all about authenticity

Empathy isn’t just about modulating how you talk to please someone else. It’s about creating a genuine human connection; about forging interesting and genuine conversations. And you can’t do that if you’re unable to express yourself naturally.

Emmanuel Hapsis writes against Wolf in an article in KQED, arguing that we shouldn’t be criticising women for the way they speak, but the people who are judging them on that criteria. He himself suffered complaints about his verbal affectations and made an effort to correct them:

The next time I went into the studio, I was so focused on these notes, on excising the bits of personal flair in my normal speech that I felt like a robot, like someone else. The authenticity was gone. Pretending to be someone you’re not isn’t healthy, especially if it’s to please others or fit into a mold that makes someone else feel more comfortable.

The lesson, it would seem, is making sure you are being yourself in the way you speak. If you’ve adopted vocal fry because it’s popular or you want to sound like Kim and Khloé, then stop, get some vocal training, and learn to talk like yourself.

If on the other hand vocal fry is part of your natural expression and range, then don’t feel pressured to eliminate it. Not everyone judges you negatively for it.

And if you find yourself hearing vocal fry and judging the speaker harshly because of it, ask yourself if you are actually listening to what is being said. Check your preconceptions and judge on substance, not just style.

As long as you research and prepare for your next meeting and don’t spend the whole time thinking and talking about yourself, then the only ‘big deal’ in the room should be the stakes on the table.