Whether you’re flying four hundred thousand miles to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons or trying to cut a better deal, the principles of negotiation are the same – meticulous research and preparation, patience, grit and a bit of neuroscience.

Successful negotiation is subtle, intuitive and complex – it’s emotional chess.

As Daniel Kahneman explains in Thinking, Fast and Slow, the slow, logical thinking – ‘System 2’ – that we usually try to employ in negotiation is actually less effective than the fast, intuitive thinking – ‘System 1’ – we tend to avoid.

So here are two ways to tap into your System 1 and use neuroscience to give you the edge in your negotiations.

Loss and reward

We are highly motivated to avoid loss.

In legal mediation, conventional wisdom says that you should threaten to terminate negotiation and take your action to trial to force the other side to reconsider your deal and to make your offer seem more attractive.

But the science says otherwise.

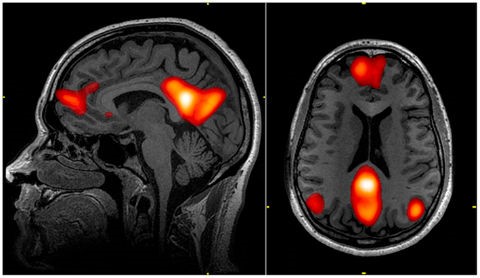

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a team at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) found that when the brain was exposed to a ‘reward’, the areas of the brain associated with pleasure were activated. But when participants were exposed to a ‘loss’, they exhibited reduced activity in these same gain-sensitive regions of the brain.

So threatening to end negotiations might, in fact, diminish your counterpart’s ability to appreciate the value of your offer.

Instead, start negotiations by going for the low-hanging fruit. If you both agree on some smaller points early on, neither side will want to jeopardise the progress made, encouraging a deal that benefits you both.

Focused but flexible

Going into a negotiation with a concrete idea of what you want sounds like a good idea, but it can actually weaken your negotiating skills.

Your concentration is a limited resource, and holding such a fixed outcome in your working memory uses up a lot of it. This cripples your ability to collaborate or see the problem from the other side’s perspective.

In practical terms, this means that you lose the off-the-cuff creativity and flexibility needed in any successful negotiation.

Of course, it’s important to pin down and put across your side’s general interests, using objective evidence and reasoning to back up your points, but becoming too charmed by your own arguments can blind you to a better deal, say researchers at UCLA and MIT. You need to stay focused while keeping your eyes and ears open.