new challenges and strategies for decision-makers

by joseph bikart

In her televised address on 5th April about the Coronavirus pandemic, HM the Queen said: “I hope in the years to come, everyone will be able to take pride in how they responded to this challenge.”

This is a question we should all be asking ourselves as citizens, family members, colleagues or simply as neighbours: how did I respond to this unique challenge? It is also the question that political leaders are constantly facing today, by friends and foes alike.

Only last week, the UK Prime Minister, whilst still bedridden in Downing Street, was accused by a newly elected Leader of the Opposition of having taken a series of wrong decisions early on in the fight against Coronavirus.

It is also the accusation being made against many leaders in Europe and beyond, including the United States, where Donald Trump is often blamed for minimising the severity of the crisis and dithering over which decisions to make.

Hard decisions need to be made, never more so than during a crisis. How leaders face these decisions today will likely define their individual leadership brand for many years to come.

In the short term, it will test their mettle, and whether they have got what it takes to steer their countries or their companies out of this crisis in the best possible conditions.

The fact that Covid-19, like many crises before it, highlights a link between crisis and decision-making isn’t an accident. It is very much by design. Going back to ancient Greece, the word that was used to mean ‘decision’ was Κρίσις, which reads as Krisis.

So, if management decisions are hard at this specific point in time, it is precisely what they are supposed to be, literally individual moments of crisis.

And at the risk of sounding like the father figure in the film “My Big Fat Greek Wedding”, I feel I need to point out that Krisis in Greek has another meaning in addition to “decision”. It is also – and rather spookily – the turning point in a disease.

The turning point of this current crisis will result from the sum of the decisions we make: How early or late it happens, with what consequences etc.

What makes decisions particularly hard in the current context is the extent of the uncertainty created by the pandemic. No one really knows how long it will last, what forms of treatment will be available, and what its impact will be on the economy and individual companies.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s research on Decision Making Under Uncertainty feels more relevant than ever.

Kahneman and Tversky identified several patterns of judgement that contribute to make our decisions much less rational than we would like to think. The following two are particularly resonant in today’s crisis.

Non-linear probability weighting

Decision-makers overweight small probabilities and underweight large probabilities. Applying this principle to the current Covid-19 crisis, we can observe that the fear that haunts most people is of catching this deadly virus. However, the UK government’s scientific advisers believe that the chances of dying from a coronavirus infection are between 0.5% and 1%.

This doesn’t minimise the severity of this pandemic, and the more considerable risk to the elderly and to people with previous conditions. But it is striking that whilst people focus their attention on this risk, they are distracted from the much more likely risks of spreading the infection through negligence, and as a result, of the health system not being able to cope with this and other conditions (see images of crammed London parks if in doubt).

There are also the real risks of government excessive indebtedness, hyperinflation and the social implications of a large proportion of the population being unable to work, including social unrest and political radicalisation.

Loss aversion

This implies that the same person who is risk-seeking when faced with a possible loss will be reluctant to take risks when faced with a possible gain. In other words, the principle of loss aversion shows that in particularly uncertain times, people may be drawn to take riskier and less rational decisions; something to keep in check in ourselves and others.

The loss aversion principle is compounded by another psychological phenomenon known as the negativity bias.

The negativity bias, also known as positive-negative asymmetry, means that we take notice of negative stimuli more quickly than positive ones, and we tend to remember negative stimuli much longer than we do others.

Think of news broadcasts in this current crisis. Invariably, they will start with the number of newly infected patients, and of fatalities. By contrast, how often do we hear about the number of people released from hospitals, once cured of the disease?

There may be a simple reason behind this: a news channel that would broadcast in equal measure positive and negative news would soon start losing viewers. That’s because, as psychologists have shown, negative news is more likely to be perceived as truthful. Start sharing too much good news and people will stop trusting you…

Our brains seem to be hardwired to receive and pay attention to bad news, more so than good news. This is because fear is an essential driver of our decisions and our behaviours. Fear has its utility. It alerts us to real dangers. At the same time, fear can be our worst enemy.

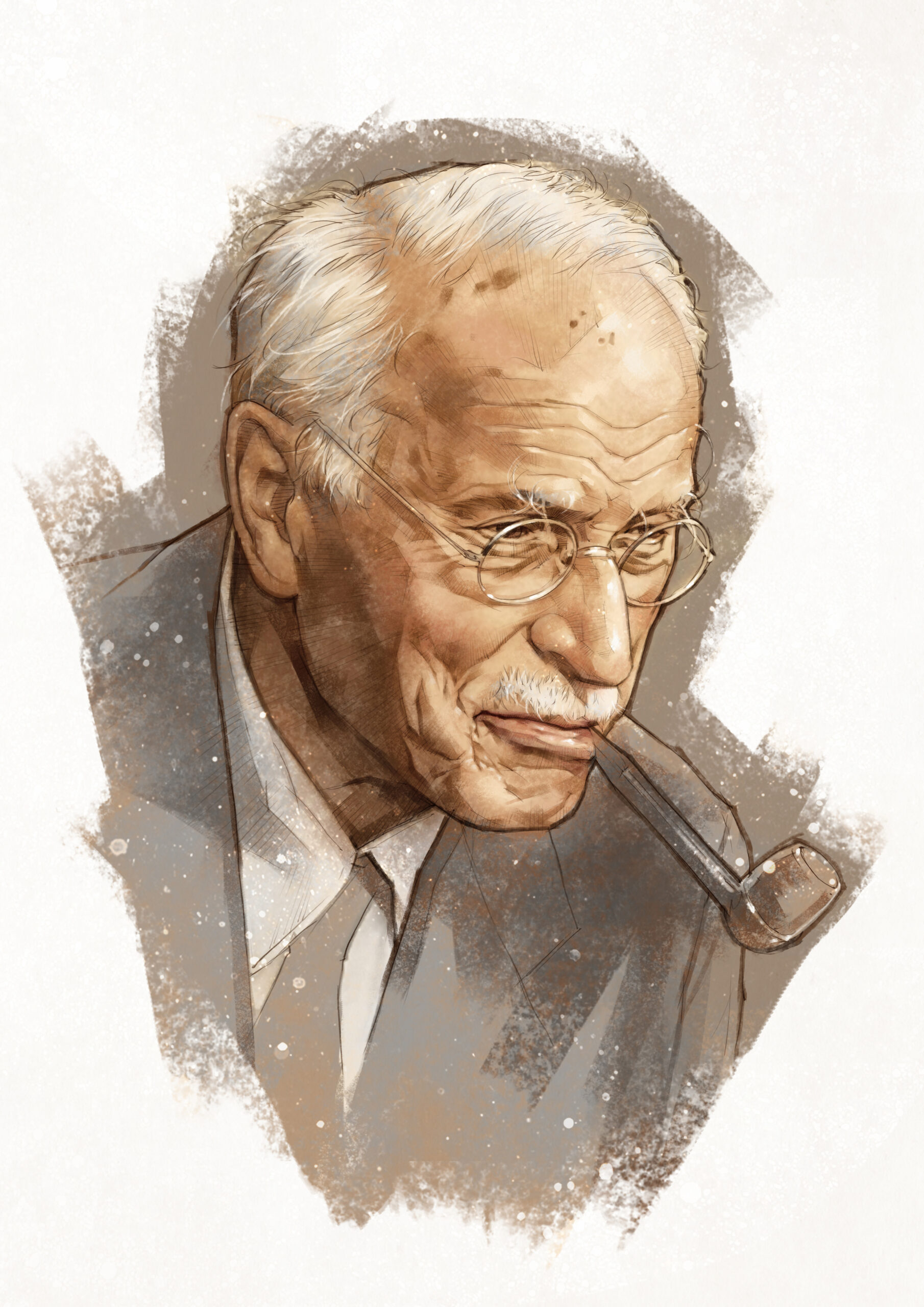

As Carl Jung reminds us, “The spirit of evil is fear, negation, the adversary who opposes life […] and thwarts every great deed […], he is the spirit of regression.”

Or to quote Sir Winston Churchill: “Fear is a reaction. Courage is a decision.”

The question for leaders today is: how do you distance yourself and your teams away from fear and negativity, towards the courageous decisions that need to be made?

I have summarised some of my ‘top tips’ here:

1. Learn from similar scenarios

This is not the first, nor is it likely to be the last crisis that we will experience. What lessons can we learn from the past? What does the experience of your company and of your sector in the last recession teach you about what may happen this year?

In 2010, two years after the start of the global recession, a team of professors from Harvard Business School conducted a year-long research to identify those companies that could best survive the crisis and discover their common denominator.

Only a small number of companies – around 9% – were doing better three years after the recession than they had done before. What this research also showed was that companies that had the highest probability of breaking away from the pack had one thing in common: they had worked out how to adapt their strategies in a way that was a perfect balance of defensive moves – e.g. selective cost reductions – combined with offensive ones like investments in marketing, R&D and new assets. (See HBR, “Roaring out of Recession”, March 2010).

2. Proximal vs distal goals

In their book Willpower Roy Baumeister and John Tierney describe an experiment that tested the relative impact of proximal goals (that is, short-term objectives) versus distal goals (long-term objectives). “It turned out,” they write, “that the distal goals were no better than having no goals at all.

Only the proximal goals produced improvements in learning, self-efficacy and performance.” Whilst facing the current crisis, it is important to remember that there is little point in making highly visionary long-term plans if they are not accompanied by realistic short-term objectives.

3. Use third parties

Self-isolation isn’t just a sanitary measure to avoid spreading the virus. It is also the unusual reality of many leaders’ professional lives today, working from home away from their most trusted advisors. This can create a warped vision of the world.

Think about the support network you need, or the useful conversations you could benefit from: maybe it is with a predecessor who has experience of similar situations, maybe it is with a mentor or an executive coach. Think about how you can broaden your ‘thinking circle’.

4. Reduce irrationality

We have seen earlier that a lack of certainty often leads to irrational thinking in decision-making. Make sure that people make thorough preparation for important online meetings, and that decision-makers’ recommendations are fact-based and do not only rely on intuition, or result from an overreaction to the current situation.

5. Take different perspectives

Think about your decisions from more than one perspective. What will the effects be on your stakeholders: your clients, your employees, your suppliers? And might you be risking your future relationship with them, in the interest of myopic short-term protective measures?

6. Challenge binary thinking

It is always tempting, when under pressure, to revert to a binary way of thinking: if I can’t do plan A any longer, then I will have to revert to B. But is there a possible third way, a plan C, that we hadn’t envisaged in previous times, but could help us navigate through this crisis and emerge from it stronger?

The hospitality sector has been one of the most affected by the pandemic. It seems that the only option for hotel and restaurant owners is to close down. But many owners have decided to think creatively and start a home food-delivery system, including luxury palace hotels like the famous Baur-au-Lac in Zurich.

Also, across Germany, many shops and restaurants are issuing vouchers that can be redeemed at a discount once the lockdown ends. A client told me recently: “how can we think outside the box, when there is no box?” It seems that it’s down to us to reinvent it from scratch.

7. Factor different outcomes

Two thousand years ago, Pliny the Elder wrote: “The only certainty is that nothing is certain”. This sounds very familiar today. Because of this uncertainty, the same causes may not produce the same effects. Therefore, try to think of how different potential outcomes may affect your business, and your employees. And factor in even those scenarios that may seem far-fetched. They may become tomorrow’s reality.

The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, admits that this is one of her preferred decision-making techniques. As Germany seems to be managing the current health crisis better than most, this is probably a model that others should follow.

As Professor Kräusslich, a leading German virologist, said in a recent interview to the New York Times: “Maybe our biggest strength in Germany is the rational decision-making at the highest level of government combined with the trust the government enjoys in the population.”

8. Communicate!

This is no time to hide. Communicate frequently and consistently. In the same NY Times article (“A German Exception? Why the Country’s Coronavirus Death Rate Is Low”, 4th April 2020), its author, Katrin Bennhold writes: “Beyond mass testing and the preparedness of the health care system, many also see Chancellor Angela Merkel’s leadership as one reason the fatality rate has been kept low. Ms. Merkel has communicated clearly, calmly and regularly throughout the crisis, as she imposed ever-stricter social distancing measures on the country.”

The same is true in the corporate world. In the City, investors will need to be reassured that companies and fund managers alike are prepared to have transparent conversations with them about the impact of COVID-19 on their businesses and portfolios. It also applies to your internal audiences: the only way to reduce the levels of anxiety among your teams is to have frequent, clear and transparent communications with them. It is also about showing compassionate leadership, rather than obsessing with the bottom line.

9. Stasis is the enemy

The last of my top tips, which summarises the approach I recommend and many of the above points, is that today more than ever, you should be seen to move, to act, to plan, to reinvent, and to communicate. In the words of Albert Einstein (from a letter to his son Eduard):

“It is the same with people as it is with riding a bike. Only when moving can one comfortably maintain one’s balance”.

Joseph Bikart is a founder and director of Templar Advisors. He is a communication advisor and qualified executive coach (Systems-Psychodynamic Coaching). He is also the author of The Art of Decision Making: How We Move from Indecision to Smart Choices.

Joseph has a background in Equity Capital Markets and specialises in working with investment banks and PE firms on their communication and executive coaching requirements. He runs Templar’s Global Investor Communication division, advising issuers on their IPO communication and corporates and PE firms as part of their M&A deals.